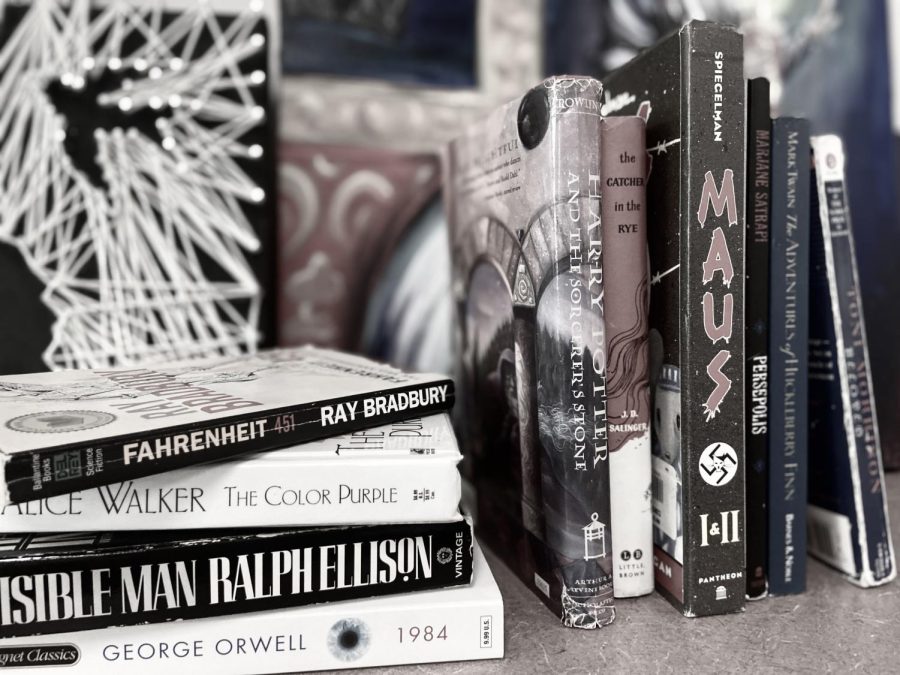

Within education, one thing has always remained the same. Rich or poor, urban or rural, left or right, books are universally and historically a fruitful academic resource used as a means of finding truth or rather personal truth. One can always step into a library, pick out a book, and develop a sense of self. However, in recent news, the faces of libraries are changing across America.

The latest wave of censorship is tackling school systems around the country at an unprecedented pace. Books are being deemed “too graphic” for student view and challenged by parents and administrators.

Art Spiegelman’s Maus, a graphic novel on the Holocaust.

George M. Johnson’s All Boys Aren’t Blue, a memoir about growing up black and queer.

Jay Asher’s Thirteen Reasons Why, a young adult novel turned TV-show, unraveling a high school student’s suicide.

Nikole Hannah-Jones’s The 1619 Project, a best-selling piece of long-form journalism on slavery and the achievements of Black Americans.

These books and many more represent the internal and external struggles of marginalized groups in America, but some people don’t think such topics are appropriate for the eyes of children or even teenagers. Some feel that these topics circulating around libraries are ones better suited for at-home discussions. They don’t want their children to be exposed to anything that may make them stray from their own ideals.

But others oppose restricting education to this extent.

Some believe that recent censorship has taken a discriminatory approach. They want to see all sides of every story, especially if a story strays from social normalities.

Parents and administration are split, their opinions on the matter varying. Book censorship has become a prevalent topic at rigorous Wake County board meetings and those of other districts around America.

Some parents are concerned that allowing students easy access to these books would introduce them to topics that are too harmful, obscene, or sexual in nature.

A parent at a Wake County school board meeting was appalled by the selection of books available to students. She felt that censorship was being opposed using the scapegoat of discrimination, saying “you allow books with sexually explicit material to remain on bookshelves, hiding under the guise that we are anti-LGBTQ– we are not.”

Other parents are concerned that censoring young minds from history will only throw rocks in the path of them seeking the truth, or rather their own truth, setting them on a direct track to ignorance and self-discomfort.

Another parent at a Wake County school board meeting felt that recent book bans are unjust. She identified the importance of libraries within education, saying “we have spaces in the school system that protect against [discrimination]; safe spaces that we call libraries; spaces where you will find representation. You will see yourself in stories. You can learn empathy by reading stories about people who are different [from] you, but only if our school district has the spine to stand against the oppressors.”

It has been difficult for these groups to find a middle ground.

Jim Martin, a Wake County board member said, “it is important to understand the laws regarding free speech. Hate speech, and threats, for example are not protected speech. But in general, no group can impose on another group what is allowed speech, in this case what might be available to read as long as it meets the legal guidance for free speech and expression, and it meets the librarian’s curation expectations and guidance.”

Many students feel that book censorship is an unnecessary denial of such rights.

“Book censorship is essentially pretty close to the removal of free speech,” said Alex Suehle, sophomore. “They’re just books. If you don’t want to read them, no one is forcing you to. If you want to read them, you shouldn’t be barred from doing so.”

Suehle argues that book censorship opens students up to being manipulated by external sources of bias.

“It removes a lot of context towards major historical events,” she said. “It allows school systems to spin whatever stories they want about events in history into whatever they want to portray. That creates a very harmful environment that only allows students to learn what a particular group of people wants us to learn.”

Rachel Surles, an English teacher at Athens Drive, too, views book censorship as an injustice to students who seek to learn their fair share from history.

Within her English courses, Surles teaches a book that has dealt with its fair share of censorship: Toni Morrison’s Beloved.

“[This book is] an exploration of what it means to deal with the history of slavery in our nation, as well as the ever-present ghost of it in our modern lives. To not read this book is to miss out on a truly unique and essential telling of an often-overlooked side of American history,” said Surles. “Yet, it has been challenged and banned regularly since its publication. I worry about books being used as political tools by people who haven’t read them.”

Many question the reasonability of banned books being taught in school. Within this subsection of the debate, it is not administrators, parents, nor even students who are facing the brunt of the controversy– it is librarians. In some cases, librarians are having their jobs threatened or even facing criminal charges for allowing banned books in their libraries.

Such librarians have opinions of their own.

Amy Myers, a librarian here at Athens Drive, said, “the current wave of banned books is an important chance for parents and educators to discuss these topics with their students. Allowing students access to these books, and these topics, opens the door for parents to have frank and necessary conversations. Further, it is also a unique opportunity for adults to talk with young adults about their thoughts on censorship.”

The political culture around censorship within schools and the threats to their careers is causing librarians and educators alike to hesitate in sharing their opinion on the matter.

“It’s this unflinching belief in the freedom of speech that sets us apart from many other parts of the world and truly represents the best part of us,” said Surles. “I think it’s a good indicator that we are entering into a pretty scary part of our history, if those who have dedicated their lives to the education of our children are being vilified and policed.”

Throughout this debate, the fact is that a line is being drawn between education and censorship. It is no simple feat to decide what children should learn about society and culture within America, and thus this debate will surely carry on to the distant future.

“Books are usually challenged by people with good intentions; however misguided these individuals may be, generally their aims are to protect others (this frequently means children) from “difficult” ideas and information,” said Surles. “However, the idea that we can protect children from “difficult”– whatever that means– ideas and concepts is preposterous. The best way to educate future generations is to have an open dialogue with them, rather than putting up dangerously high walls to protect them.”