The classic struggles of high school students are known universally. From movies to real life, everyone has faced the struggles of crowded hallways, pit stains, and tardy bells. However, some classic high school experiences are unique to only half the population. Namely, the dreaded moment in which a teenager is caught on the first day of their period without a pad or tampon on hand.

Laura Bernstein, art teacher, recalls her first period experience from 4th grade with a laugh.

“I had no idea what it was because my parents had never had the sex talk with me and the only reference I had was the movie ‘My Girl.’ There’s a scene in ‘My Girl’ where a little girl gets her period and starts screaming that she’s hemorrhaging because she doesn’t know what’s happening.”

She recounts the event lightheartedly, recalling her emulation of the scene as she, too, jumped up in the cafeteria screaming that she was hemorrhaging. She was intercepted by an older girl who convinced her to sit on a conveniently present bag of Cheetos, then a pile of grass in an attempt to hide the stain.

“So throughout the day, I had blood, Cheetos, and dirt all over my butt and that was my first period,” said Bernstein.

Bernstein’s is just one of many stories involving confusion and stress that face young women caught empty-handed on their periods. Fortunately, Athens Drive’s very own are working to solve this problem.

Rhizome, an organization intended to support and encourage high school involvement in civic engagement, has previously held events such as mental health week and meetings to educate high schoolers on issues such as rank-choice voting and voter ID. Rhizome’s most recent project is to gather and organize menstrual products in all bathrooms at the Drive so students have public access to period products in bathrooms.

“Period products can be extremely expensive, making them less accessible for low-income people. Also, it’s extremely stressful having to find them when you don’t have any,” said Zoe Som, president of Rhizome.

While the access provided will cause a collective sigh of relief amongst those students who have been caught off guard or forgotten a pad on their period, initiatives such as this one can have much bigger social impacts. Many teens struggle from the inability to access such products on a consistent basis as opposed to random inconveniences. A study released by period product brands Thinx and PERIOD showed one in five teens struggled with access, 23% of teens interviewed said they struggled to afford period products, and 16% said they chose to buy period products rather than food.

“Making period products free reduces the stigma around periods, we shouldn’t be ashamed to talk about it, especially if half of our population has to deal with it,” said Som.

Beyond keeping period products out of the hands of those who need them, Bernstein cites the intense amount of shame she faced as a teenager with her period in the 90s. Beyond the child-like tendencies of kids at her age to find any bodily function laughable, she also faced the grasp that previous generations had on the way she should perceive her body. Teachers, and even parents, maintained a “keep mum” mindset on the topic of periods.

As Berstein continues to relive her first period, it also occurs to her that this might have been prevented had she known what her body was going through. However, her mentors had maintained that it was simply too taboo to be worthy of education.

“I came home and my mom was pissed about the white shorts, of course, that’s what she was upset about. She still didn’t tell me what was going on. She put a book on my bed about getting your first period and then walked away,” said Bernstein.

Studies even show that trends in media and advertising suggested that period leaks “tainted” or “contaminated” one’s femininity, and that overall, women were treated more restrictively to maintain their propriety and “ladylikeness.” This gave birth to a necessity for women up until the 90s to hide their period if they were to maintain their good social standing.

From making sports uncomfortable to facing bullying from young boys who saw her period as “dirty” or “gross,” Bernstein experienced firsthand the consequences of considering periods shameful, with no one to support her through such a landmark transition

“I never would have gone to a teacher and asked for a pad. I wouldn’t have even thought to even though I’m sure they had them,” said Bernstein.

While recent feminist movements have helped alleviate the stigma surrounding periods, cultural differences in the treatment of periods still exist. The students organizing the project are not only providing products but are also crossing cultural thresholds in the hopes of making every student a little more comfortable with tackling the struggles that come with hiding periods. With a population as diverse as the one at Athens, these students are not only tackling societal views on periods but also deeply rooted cultural ones.

Eyman Sakr, freshman, is a half-Egyptian and half-American Muslim student who has seen the subject approached from both angles.

“With periods, sure there are things like no praying, no fasting, but part of it is the overall culture. I went to an Islamic school and there was always a stigma of ‘ugh, periods are gross’, but it was more the culture of the place than the religion.”

Sakr recounts a story told to her by a friend, whose uncle was fasting during the month of Ramadan. Like Sakr’s friend, Muslim women on their periods will traditionally not partake in fasting. However, in the presence of her uncle, the young girl did not eat to avoid him realizing she was on her period.

“Why does she have to suffer because this grown man can’t handle the fact that she’s bleeding? I was so angered by that,” said Sakr. “I don’t like when people say something is because of religion when really it’s because of the way people are raised.”

The ever-changing cultural perception of periods continues to influence discourse around the world. Women in India face brutal scrutiny while on their periods, with consequences such as high taxes on period products, denied entry to public areas such as kitchens and places of worship, and high dropout rates for girls who have gotten their first period. Meanwhile, countries such as Japan and South Korea have historically introduced period leave into their labor laws, yet social stigmas surrounding periods and taking leave from work result in minimal use of such conveniences.

Principal Steven Mares, citing similar concerns on the cultural differences in the treatment of periods, believes easy access to products will allow individuals to deal with their period without giving up on their comfort or security.

“We have students that come from all over the world and don’t necessarily want to tell somebody, that might be a cultural aspect, so to have that there… is just one less thing people have to worry about,” said Mares.

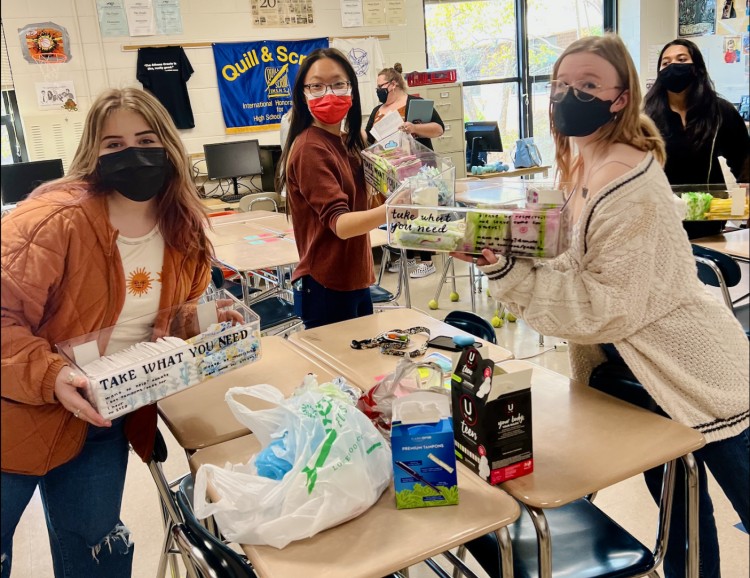

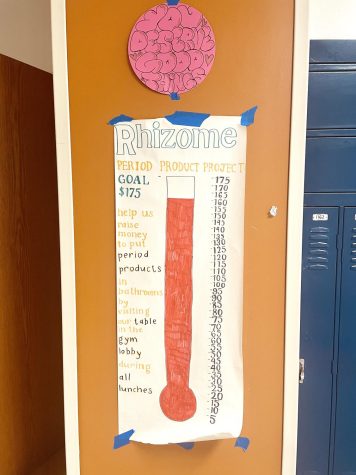

To sustain the project, Rhizome collected funds and period supplies at a table in the gym lobby during all lunches Feb. 7-11. Funds will be used to purchase baskets and storage as well as any extra products necessary. Donations will continue indefinitely to supplement the product bins, and all supplies can be dropped off in room 2420. By February 11, the team had collected over 2000 pads and tampons to store in bathrooms.

However, despite its initial success, the team emphasizes how vital it is that they continue receiving support.

“We need to work extra hard to ensure that there’s school-wide engagement so we can get enough money to buy bins to store the products in and enough donations to stock the bathrooms and restock them when needed. We also need to make sure we’re keeping track of how long supplies last so we can keep a constant supply of pads and tampons,” said Som.