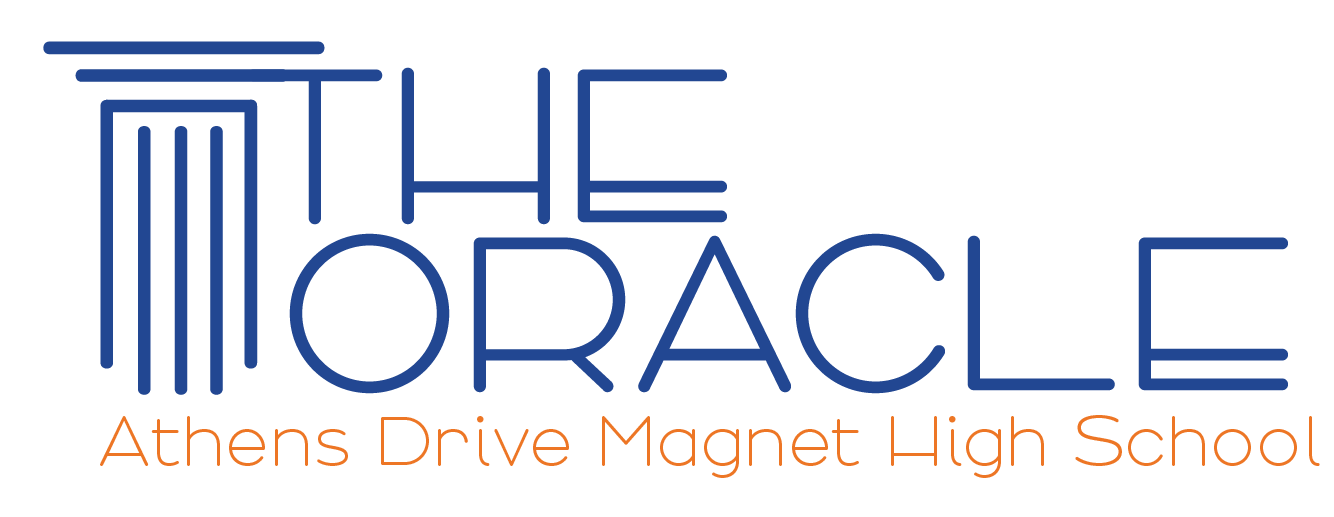

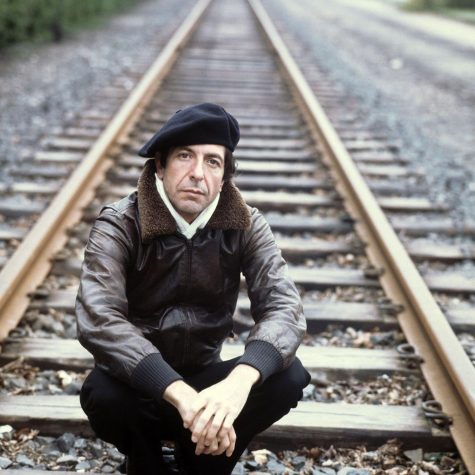

In all of singer-songwriter Leonard Cohen’s discography, the song Take This Waltz (included in his 1988 studio album I’m Your Man) seems negligible. It exists in stark contrast to his more popular or folksy songs, most notably Hallelujah or So Long Marianne. Cohen encapsulates a formal, almost luxurious tone in Take This Waltz, and yet the lyrics are where it shines. Like most of his songs and poems, Cohen features verse after verse of fanciful lyrics in the song. It is a surprise then, that the lyrics are not his– not really.

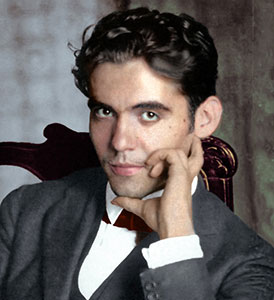

Federico Garcia Lorca was a poet born in 1898 in the southernmost region of Andalusia, Spain. He was most known for the romanticism and surrealism of his works, including his book of poems entitled Romancero gitano (Gypsy Ballads). It is no wonder then that Leonard Cohen, a self-described “born poet” was attracted to Lorca’s work. “His books taught me that poetry can be pure and profound – and at the same time,” Cohen said about Lorca, even going so far as to credit discovering Lorca’s work as the catalyst of his musical career.

Take This Waltz is a prime example of Lorca’s influence on Cohen’s work. The song is a loosely translated version of Lorca’s poem Pequeno Vals Vienés, or Little Viennese Waltz. “I noticed what a complex writer he was,” Cohen noted about the writer. “It took me more than a hundred hours just to translate the poem.”

Many sympathize with Cohen in his inability to capture the true essence of Lorca’s writing through translation. His poem Rider’s Song describes the brief scene of a horseman riding into Cordoba, where he knows death awaits him. There is no explanation as to what death awaits him or why. Yet, Lorca’s prose is haunting as he ends the poem with a single-versed stanza: “Cordoba, far and lonely.”

Lorca’s influence is present in almost all of Cohen’s discography. In his debut album Songs of Leonard Cohen, his influence is at its most obvious. The song Stories of the Street captures small vignettes of seemingly nonsensical moments, all pieced together in a surreal way. Here are two separate verses from the song:

“The stories of the street are mine / the Spanish voices laugh / the Cadillacs go creeping now / through the night and the poison gas / and I lean from my window sill in this old hotel I chose / yes one hand on my suicide, one hand on the rose.”

“O come with me my little one / we will find that farm / and grow us grass and apples there / and keep all the animals warm / and if by chance I wake at night and I ask you who I am / O take me to the slaughterhouse, I will wait there with the lamb.”

There is an obvious comparison to be made between Stories of the Street and Lorca’s Ghazal of the Morning Market, which reads as follows:

At the Gate of Elvira

I want to see you pass,

so to know your name

and begin to weep.

What pallid twilight moon

bled your cheek to death?

Who gathers your seed

of flash fire in the snow?

What quick cactus needle

murders your crystal?…

At the Gate of Elvira

I’m going to see go by,

to drink in your eyes

and cry.

What din you raise to

castigate me in the market!

What deranged carnation

in the mounds of wheat!

How far when I am with you,

how near when you go!

At the Gate of Elvira

I’m going to see you go by,

to feel your thighs

and cry.

Both the rhythm and nonsensical nature of Lorca’s poem are strikingly similar to Cohen’’s own prose; and it works. Leonard Cohen says it best himself. “It was only when I read, even in translation, the works of Lorca that I understood that there was a voice. It is not that I copied his voice; I would not dare. But he gave me permission to find a voice, to locate a voice, that is to locate a self, a self that is not fixed, a self that struggles for its own existence.”