This past November 6th earned a disappointed sigh from many Americans, leaving behind it an air of apprehension. The 118th congressional elections reintroduced one of the many seemingly contradicting concepts of American Government: a divided Congress to govern over a single country.

After a term of Democrats holding the majority in both the Senate and House of Representatives, the Republican party has gained control of the House. Now, as the House bleeds red with tradition, and the Senate bleeds blue with modernity, the American government– the system of justice, the root of legislation, the backbone of our ideals– is split down the middle.

But, is that really such a bad thing?

Political socialization is a growing aspect of American culture and, practically, education is a leading contributor of such enthusiasm. The result? What most Americans with a commonplace comprehension of governmental procedures know about the construct of a divided government is just about as far as the curriculum of a high school civics class allows.

A divided government slows the legislative process.

A divided government encourages tension between opposing political parties.

A divided government is a recipe for gridlock.

Those criticisms do hold some ground. If we were in a different time, I may actually agree. But in 2023– when the cup that is American politics has far since overflowed into the everyday lives of ordinary citizens– I invite you to look at the notion of a divided government from a different perspective.

America’s founding fathers were against many constructs that are visible within American society today. They built this county with the understanding that no one person, nor institution, should hold too much power over the governmental directorate, solidifying the establishment of checks and balances.

A single party holding Congress within its two fists is a far too precedent occurrence, but one that, I think, contradicts the logic of American origins. And though the founding fathers didn’t approve of the notion of political parties, that ship has far sailed, and we can still allow democracy to thrive in such a climate. How? By allowing both parties to hold their grounds.

A divided government may seem wholly insufficient and conflicting term to describe a supposedly united group of people, but in actuality, it is quite fitting for American culture because America, today, is not united.

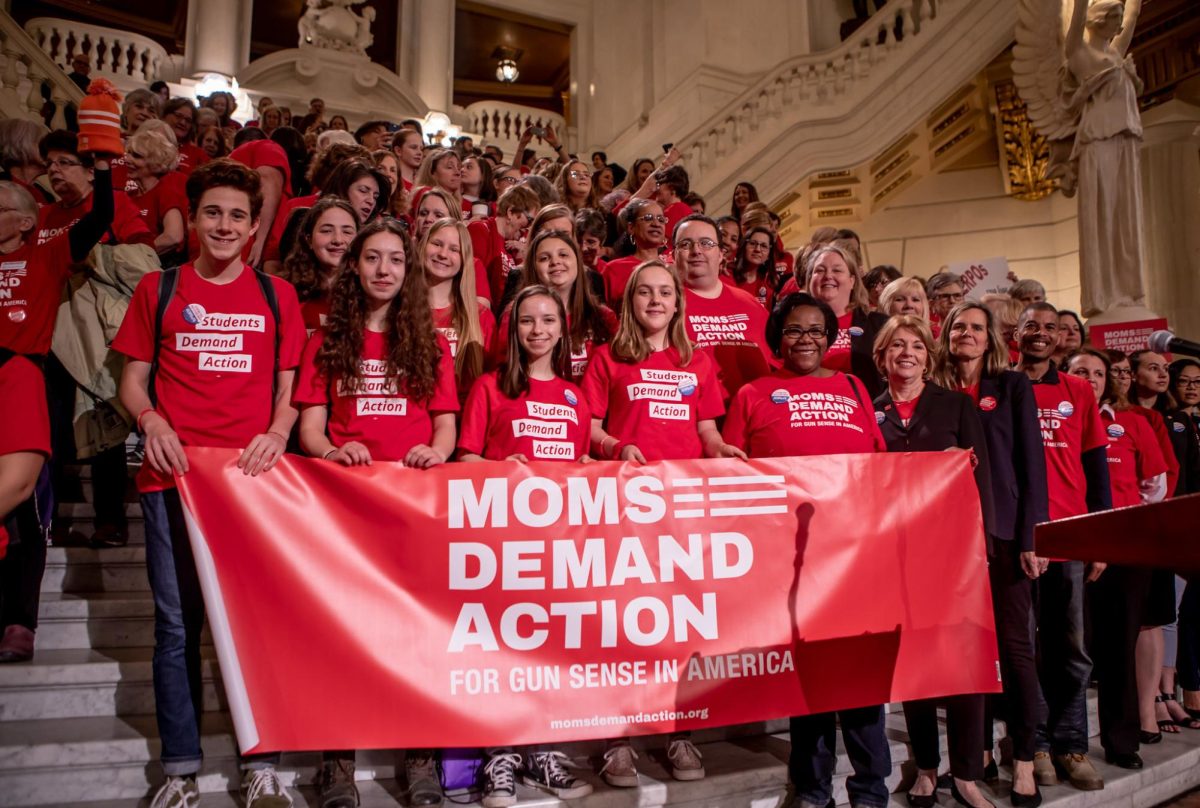

The tensions within classrooms, coffee shops, and computer screens are so thick they could be tangible. Your political standings make way before you do. People, businesses, and institutions make sure to mark themselves with telling signatures of blue or red: a banner upon entrance of a rainbow, or a washed out American flag with a single blue stripe– a subtle challenge, daring someone to protrude.

Our people are far from united, so why advocate for a united government?

In truth, a united government would be the real goader of aggression. Letting one party hold power over both houses of Congress– tackling both the Senate and House of Representatives, given free reign to push the legislation of their will upon the entire country with little to no pushback possible from the minority party– is what really stimulates resentment and, therefore, division. And, to me, that sounds a lot like corruption.

The government is more efficient than you’d think during a divided government. It prevents impulsive legislation from making its way through Congress to impose itself on people with opposing viewpoints as occurs during a united government. And, still, many successful forms of legislation have been passed by both parties during periods of congressional division.

The Democratic Party, over the years, has passed wide-reaching bills that complement their standings in the midst of a divided government: The Affordable Care Act, The Inflation Reduction Act, The Green New Deal, etc.

As has the Republican party: The Taxpayer First Act, The Bankruptcy Administration Improvement Act, The Due Process Protections Act, etc.

Giving both sides a seat at the table of legislation and opening the doors to debate, to compromise, should be the natural way to govern under division. Rather than aggression, it lays the groundwork for progression and we can see that in real-time. Under a divided, bills like the Criminal Justice Reform Act or the Infrastructure Package have been passed with bipartisan support.

In times like these, this is how the government should be functioning: demonstrating to the general public that you do not need to completely agree with someone to compromise with them, to find companionship in them, to– at the very least– offer decency to.

The knots and kinks work themselves out.

Under a united government, speed would be of the essence, immediate tensions would be avoided, and stalemates wouldn’t be a concern, but divisions would be seared through the American map, concession would be off the table and the ideals of democracy would be held in contempt.